At Nor-Shipping in April this year, one of the few new product launches was Saab Transponder Tech’s new R6 Supreme system. It is a new generation of shipborne Class-A Transponder system that is type approved for AIS and prepared for future VDES functionality and therefore will be key to future e-navigation systems.

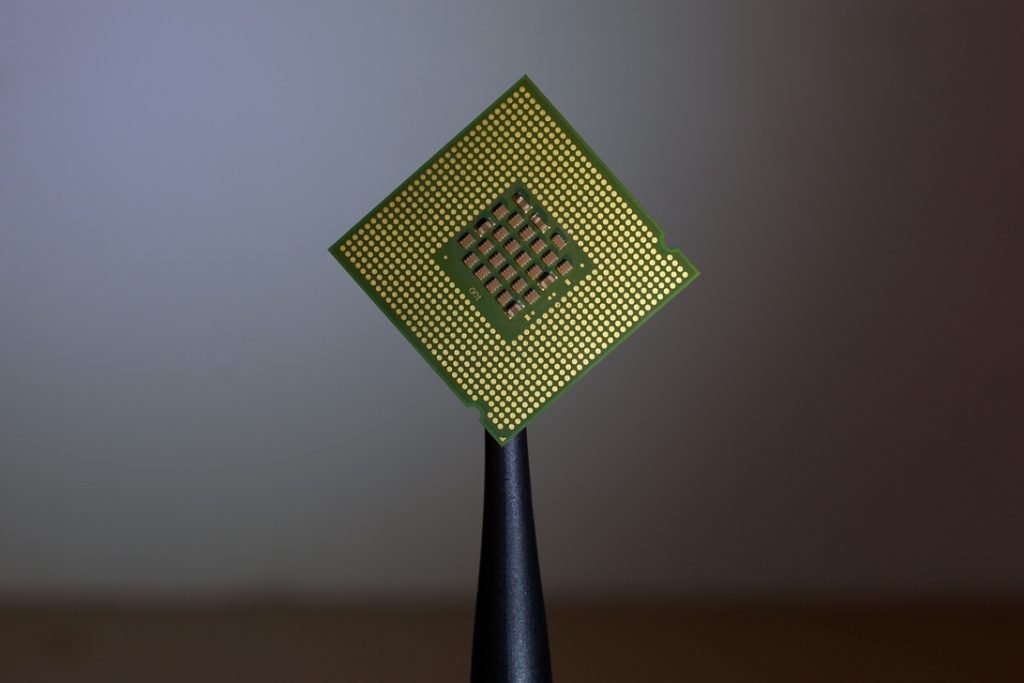

Questions about its availability revealed that production is being slowed by a shortage of semiconductor chips and while every effort was being made to secure supplies, product rollout may inevitably be delayed.

Saab is not alone in being impacted by the shortage of chips as other companies including Kongsberg Group have mentioned electronic component shortages as likely to affect future sales and financial figures.

In recent years, shipping has moved from an almost entirely analogue industry to one that is becoming increasingly dependent on electronics. With very few exceptions, all main engines fitted to new ships are electronically controlled.

Performance monitoring as a means of reducing fuel use and controlling emissions is seen as being one of the strategies that ships will need to employ to meet the impending Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) when it comes into full effect in January 2023.

E-navigation is still in its infancy but the rollout of ECDIS which is at its heart was begun in 2012 and completed in 2018. Since an ECDIS is really little more than a sophisticated computer, many of the early installations will soon be due for renewal. Electronics will also be a core component of any autonomous ships that are planned to come into operation.

In fact it is fair to say that although shipping is said to be behind other industries in digitalisation, there is almost no aspect of ship operation that does not depend upon some element of electronic management.

The chip shortage has now been with us for almost two years and does not appear to be closer to resolution. Initially blamed on a surge in demand for computers as people were obliged to work from home during the pandemic, there is now almost no industry that has not been impacted in some way. The need for more computers came at a time when almost all of the main semiconductor makers were experiencing a whole variety of problems ranging from fires to drought causing production shutdowns.

Production still has some way to go to reach pre pandemic levels but even if full capacity is reachable, there are more obstacles to overcome. Manufacture of semiconductors requires lasers which use neon. Most of the world’s neon is produced in Ukraine and production has been hit hard by the conflict there. Alternative supplies are being sought but success has been limited and with 90% of US semiconductor production previously relying on Ukrainian neon ramping up must be delayed more. As a consequence of the sanctions imposed on Russia for the invasion, another aspect of chip production has been impacted as Russia exports about 40% of the global supply of the metal palladium, used in certain chip components.

Returning to shipping’s use of electronics and its need for semiconductors, it should not be forgotten that communication equipment is among the systems certain to be affected by a chip shortage. Whether it be for antenna operation or the transmission and receiving hardware chips will be in short supply. That could affect all ships both new buildings and existing vessels.

Few ships have the capacity onboard to repair complex electronic equipment as most have opted for repair contracts with equipment suppliers or specialist service providers. Regardless of repair resources, if chips are damaged and new PCB’s or components needed a shortage of essential electronic components could mean that ships are operating without mandatory equipment. In some cases that could lead to a ship being detained until a replacement part is sourced.

Semiconductor manufacturers have said that they hope the situation will improve at some point in 2023 but there is no certainty of that happening. Although the world fleet has been expanding for many years, with only around 100,000 to 150,000 ships making up the global fleet it is hardly a major customer. Marine equipment manufacturers will be in fierce competition with every industrial sector for supplies once they become available and are not guaranteed to be at the head of the queue.

It may well be a good idea for ship operators and ships’ crews to take stock of the equipment onboard and ashore that they consider essential and investigate the replacement and repair capacity of the equipment maker. If they are told there may be problems, then perhaps a search for an alternative supplier might be in order or even investing in a duplicate piece of equipment that can be kept onboard and substituted in the event of a failure.